A Q&A with Shaun, our director

Dr Shaun Fitzgerald is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering who works at the interface of academic research, business, government policy and public engagement. He has worked extensively in the commercialisation of new intellectual property arising from university research, and supported the UK government in the re-writing of policy documents for building ventilation standards. Before joining the Centre for Climate Repair in 2020, Shaun was Director of the Royal Institution, overseeing the programme for engaging the public with science and engineering.

In this Q&A, Shaun discusses the Centre's mission and values, the importance of innovative approaches to climate change, and why he believes these efforts are critical for our future.

Why do we need the Centre for Climate Repair?

What persuaded you to pursue this area of research?

How could we ‘refreeze’ polar ice?

Is geoengineering a solution to climate change?

What kind of scenario could trigger a climate intervention?

Who should decide if these technologies are deployed?

Are you concerned that they could be misused to delay the phase-out of fossil fuels?

How hopeful do you feel about the climate future our kids and grandkids will inherit?

Why do we need the Centre for Climate Repair?

"We need the Centre for Climate Repair to ensure we have a holistic, overarching strategy for tackling climate change. All the scenarios now considered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) see us going through 1.5 degrees centigrade of warming. Rather than just resigning ourselves to that, we need to at least explore whether there's an alternative. The Centre’s purpose is to look at the role of what we call the ‘three Rs’ and enhance our knowledge of each.

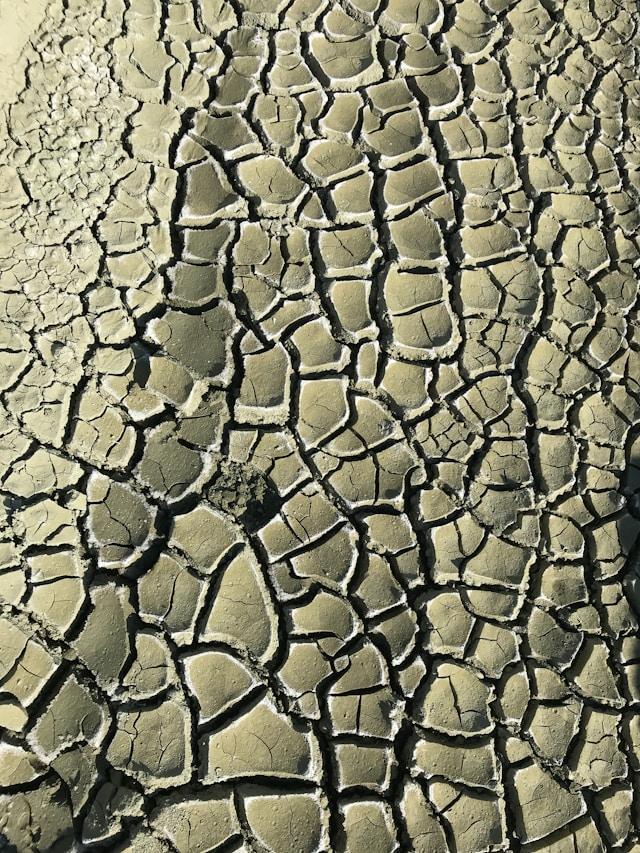

"The first ‘R’ is to reduce emissions. The second is removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. The third is what we call ‘refreeze’: exploring ideas for keeping the ice on Greenland or Antarctica while we're getting greenhouse gas levels down, so that we don't experience sea level rise and all of the other effects of climate change. This is often called climate engineering, climate interventions, or geoengineering."

Back to top

What persuaded you to pursue this area of research?

"I spent nearly all of my career in emissions reductions before realising that we are going to need to do more than that. I spent the first part looking at geothermal power, and providing energy without fossil fuels. In the latter part, I spent time on how to create more energy-efficient buildings. But I realised from talking to colleagues here in Cambridge that reducing emissions is necessary, but not sufficient. Don't get me wrong – we need emissions reduction like there's no tomorrow. But we need to equip society with other options as well."

"I spent nearly all of my career in emissions

reductions before realising that we are going

to need to do more than that... We need to

equip society with other options as well."

How could we ‘refreeze’ polar ice?

“There are ways that we might be able to help keep ice in those polar regions, by thinking about the Earth as one big chamber that is getting warmer. Can we reflect some of the sun's radiation away from the Earth before it has a chance to continue to warm? If we can reflect just one or two percent of the sun's radiation back into space, it will have a huge impact, reducing the temperature by one or two degrees celsius.

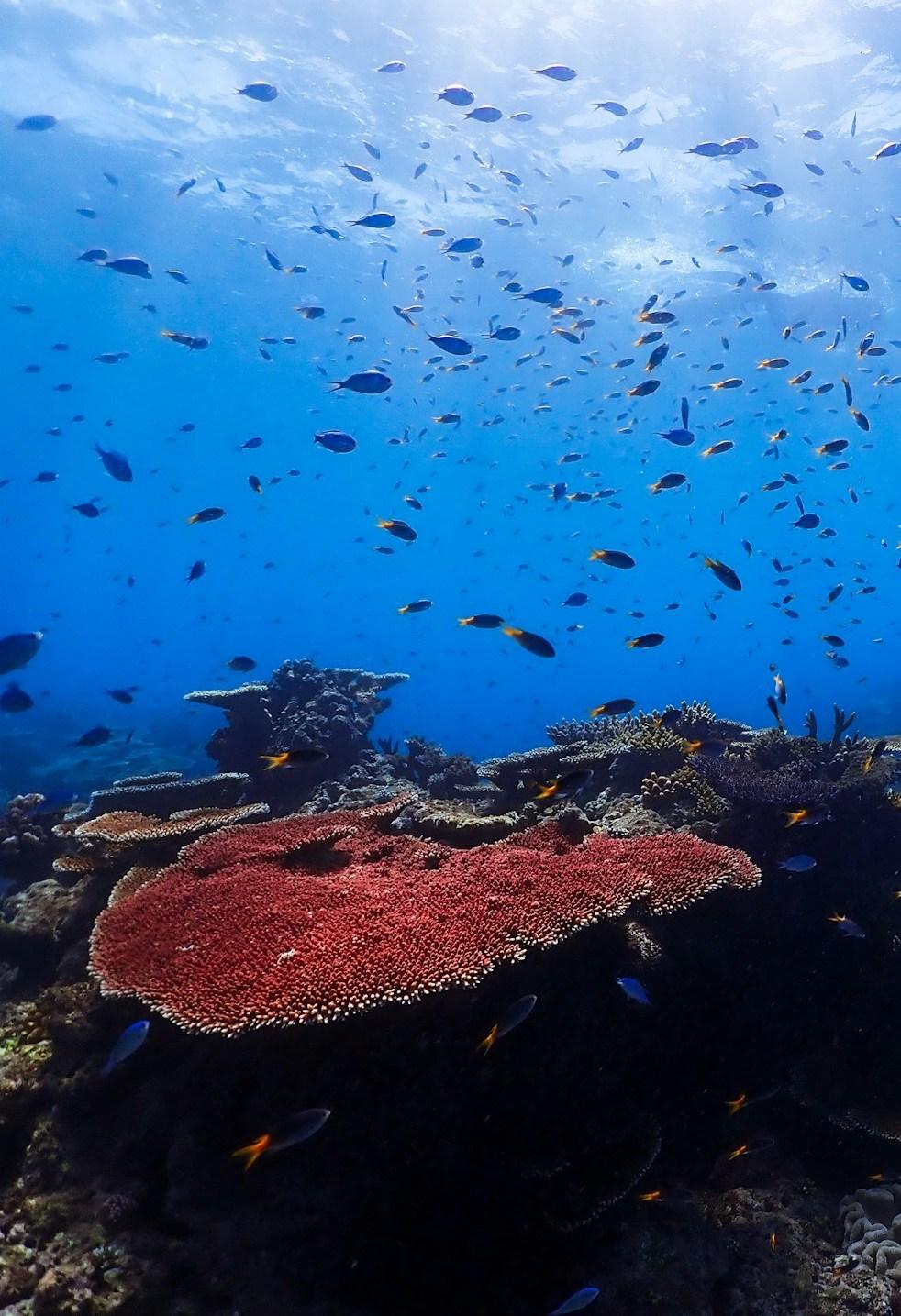

“For example, we're looking at the way that clouds above the ocean reflect the sun's radiation. If you can arrange these clouds to be comprised of more, smaller droplets, rather than fewer, larger ones, then those clouds appear whiter; they're optically brighter. So, the big question is, how would you get those clouds to be formed of more, smaller droplets? This is an approach called ‘marine cloud brightening’.

“We've got technology being developed here in the University of Cambridge focused on different droplet generation methods for marine cloud brightening which are looking encouraging. We’re optimistic that we'll have something within the next two years that we could put on a boat and try out in the field, and I'll be surprised if it isn't better than the existing technology. That's not guaranteed, but I'm excited about that.

“And another is ice thickening. Our colleagues Real Ice have done two look-see experiments, one in Alaska, one in Canada, over two different winters. And the initial signs are that, yes, we know how to pump water onto the ice and get it to freeze from above.

“I think those are two approaches that are potentially going to be available in the nearer term for society to consider whether they could be deployed or not.”

“[Geoengineering] approaches are like... the measures you

need to put in place to keep a patient alive whilst you sort

out the underlying problem.”

Is geoengineering a solution to climate change?

"These approaches are not the solution to the climate problem; they’re like a band aid. Greenhouse gas levels have got to be brought down, through reduction as well as removal. The area we call ‘refreeze’ is the band aid. As some doctors have said to me, it’s a bit like the measures that you need to put in place to keep a patient alive whilst you sort out the underlying problem. If some of them, or even one of them, works, then that's a really great thing. It might not solve everything, but it’s just buying a bit more time to get those greenhouse gas levels down."

What kind of scenario do you imagine could trigger a climate intervention?

"One idea that scares me is that a country devastated by climate change could try some sort of climate intervention out of desperation. This could be, for example, after multiple years of flooding, with crops having failed, saltwater decimating the land, and millions of people affected. In an act of desperation, they give marine cloud brightening or stratospheric aerosol injection a go, without knowing if it will work, because they’ve got to try something.

“And it's that trigger point that exercises me most, because we absolutely need to know more about these technologies. As much as the research might teach us how these ideas can work, it could also teach us why they're a bad idea, because of the increased risks of other things happening. So, our furtherance of knowledge is not there just to promote the technology. It's to provide greater clarity, to make it easier for society at large to make more informed decisions.”

“As much as the research might teach us how these ideas can

work, it could also teach us why they're a bad idea. We absolutely

need to know more about these technologies… to make it easier

for society at large to make more informed decisions.”

Who should decide if geoengineering technologies are deployed?

"Let's say a technology is shown to be looking very, very helpful. There needs to be a judgment on a balance of risks and benefits as to whether it should get deployed or not. Those conversations certainly don't need to involve just academics, and we need to ensure we've got the right people around the table. They need to involve policymakers, and you might have ethicists and economists, and importantly, different voices around the world. In particular, those who are on the front line, facing the effects of climate change; the people least able to adapt or withstand them.

They might be a minority voice, but I think they should have a big seat at the table, certainly as to whether the research gets undertaken. And if research reaches a stage regarding trials for deployment, they need to be involved heavily in those discussions and decisions. Academics might just be advisors on what we know about the science, and not involved in decisions about deployment."

"Those who are on the front line facing the effects

of climate change should have a big seat at the table...

As a minimum, we need to be working with local

stakeholders and involving them in research."

"As a minimum, we need to be working with local stakeholders and involving them in research. The Centre for Climate Repair has had the privilege of being involved as guests in two programmes that involve and lean upon local communities. One was marine cloud brightening over the Great Barrier Reef, where First Nations people were on board the boat, supporting and helping to guide the research. And also ice thickening research in the Arctic, where decisions as to whether the team went out onto the ice on any given day were led by the local Hunters and Trappers organization, who were in charge of the programme. Ultimately, I would love to be in a position where even the research is being led by local communities and people on the front line of climate change."

Are you concerned that geoengineering technologies could be misused to delay the phase-out of fossil fuels?

"Yes, I am. This argument is sometimes called the ‘moral hazard’. This is the possibility of developing technology which can help stave off the worst effects of climate change, perhaps even cool the earth a little bit, maybe refreeze the poles, but which then results in a weakening of our resolve to get off fossil fuels. That's the argument that I hear most commonly. I am concerned about it, even though the evidence base for it might be questionable.

"But I don't think this is a moral hazard challenge on its own. We also have the problem that there are countries that in all likelihood are going to disappear in the next 50 years, due to ice melting from Greenland and Antarctica. At COP 28 in Dubai, I had the privilege of attending a speech by Ilana Seid, the United Nations ambassador to the islands of Palau. And she said two things: First, that for her people, one or two metres of sea level rise is not a case of losing a bit of beach, but a country. And secondly, that asking for a prohibition of funding and research on geoengineering ideas is akin to asking: 'Please trust the global north and big polluters to reduce emissions faster than any scenario now considered by the IPCC.'

"I find that idea really alarming. To me, it comes across as a colonialist viewpoint. There are people calling for support and research into these ideas, and we have a moral obligation to do what we can to try and keep these islands without being swamped by rising sea levels. So, we don't have just one moral hazard; in a way, we have two."

“Asking for a prohibition of funding and research on

geoengineering ideas is akin to asking: 'Please trust

the global north and big polluters to reduce emissions

faster than any scenario now considered by the IPCC.'"

How hopeful do you feel about the climate future our kids and grandkids will inherit?

"I sometimes see reactions to climate change that concern me. There are people who say, ‘Well, it’s all going to hell in a handcart, but I'm not going to be here in 50 years’ time, so why should I bother trying to change anything?’ And then there's another reaction: climate anxiety, especially in younger people; just feeling really worried, and that worry eating away at them. And that's why I think this is worth caring about. Because, we can do something about it. To help people who are in both those camps, we’re going to give you some options.

"So, am I hopeful about the future? Yes, I am. I can’t promise that we’re going to be able to keep us below 1.5 degrees centigrade, because we haven't got the knowledge yet to know whether some of these approaches might work. But I'm hopeful that we're going to be able to make it a lot less damaging than it would otherwise be. I'm optimistic that even in five years, we can have something that is demonstrated in the field, and society could be making a decision as to whether it should be scaled up or not. And in 10 years’ time, they could be operating at scale to start making an impact on the climate. And that's why I'm in the job that I am, because I think it is something we can make a big difference on."